Screams pierced the foggy San Francisco air.

I raced to the beach to find my friend Blake lying immobile in a pool of blood, a long piece of driftwood piercing his side. A fresh wave of blood squelched forth with every shallow, shivering breath, his blue eyes glazed with pain.

More screams echoed from the water where a woman flailed desperately, one hand clutching her bloody face.

There were bodies everywhere. Blood on the sand, blood in the water, and no help in sight.

–––––––––––––

Thankfully, the blood was fake. So were the screams. In fact, the whole thing was fake — this was just another day in WFR class.

What’s a WFR?

WFR, pronounced “woofer,” stands for Wilderness First Responder, an 80-hour wilderness medicine certification from the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS.) Most professional outdoor guides, from whitewater rafting instructors to backpacking trip leaders, are WFRs.

They call wilderness medicine “MacGyver medicine” because it’s so different from medicine in civilization.

You won’t learn how to start an IV or slice someone open for surgery because you won’t have those tools in the middle of nowhere. Instead, you learn to do the best you can with what you have. (You do get CPR-certified and learn to operate an AED, though, just in case.)

Why I decided to take a WFR class

In wilderness medicine, you’re more likely to be saving the life of someone you love. If a hiking buddy or my dad gets hurt in the wilderness, where real medical help is hours or even days away, I want to be able to do something. (And if I meet an injured stranger in the woods, I want to help them, too!)

I’ve also had a few close calls.

I drove two friends to the hospital with injuries in the same year — one with a nasty shoulder dislocation after leaping down a ledge in Yosemite and the other with a broken ankle after a similar fall in Tahoe.

Both times I raced down a steep mountain in the dark with no lights or guardrails, trying to get to a hospital fast but not too fast because every time I hit a bump the friend would groan in pain. Both friends were fine, but it got me thinking. What if this happened 10, 30, or 50 miles from the nearest paved road? What would I do then?

My WFR Class Experience: 9 Bloody Days at Crissy Field

The Wilderness First Responder course is like bootcamp for your brain: 80 hours of instruction over 9 days, plus reading and homework.

“I haven’t studied this much since college,” my silver-haired classmate Linda laughed. “And college was a lot longer ago for me than it was for you!”

It’s a mini-medical school, where you’re thrown into a swirl of symptoms and solutions and, most importantly, scenarios.

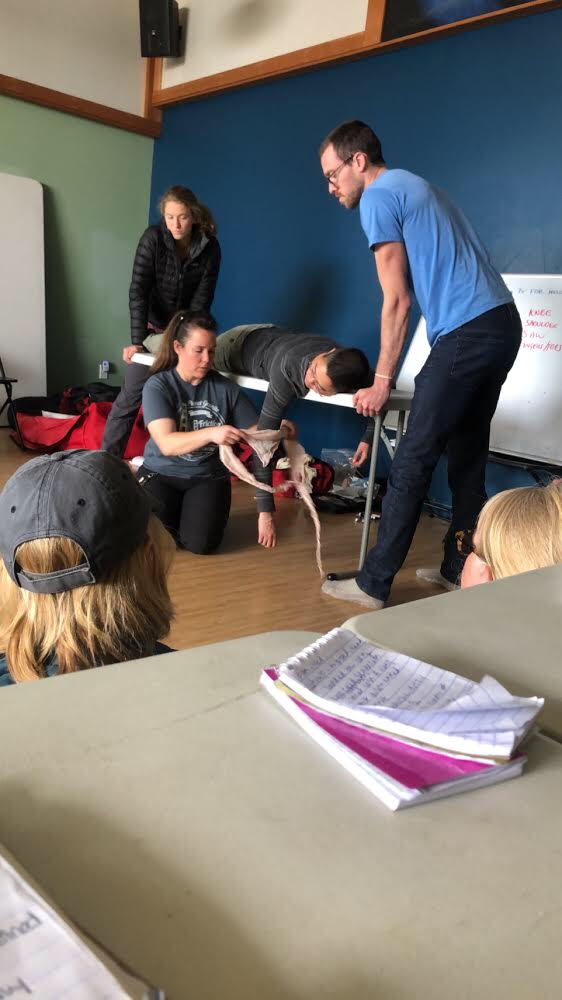

Scenarios are detailed scenes where you practice responding to incidents, alternating playing patient and playing WFR.

I played, among others: a plane crash victim, a drowning survivor, a septuagenarian thrown from a mountain bike, and a little kid who’d eaten too many marshmallows (a red herring) and then been kicked by a horse (the real injury, revealed only during a head-to-toe exam.)

We made human burritos to treat hypothermia, splinted arms, taped ankles, administered Epi-Pens, and called (imaginary) helicopters for victims of acute altitude sickness. Patients “died” when their wannabe WFRs didn’t administer the right treatment in time, which was surprisingly stressful for fiction.

“The more you “die” here,” our instructor Nissa reminded us, “the less likely someone will die in real life.”

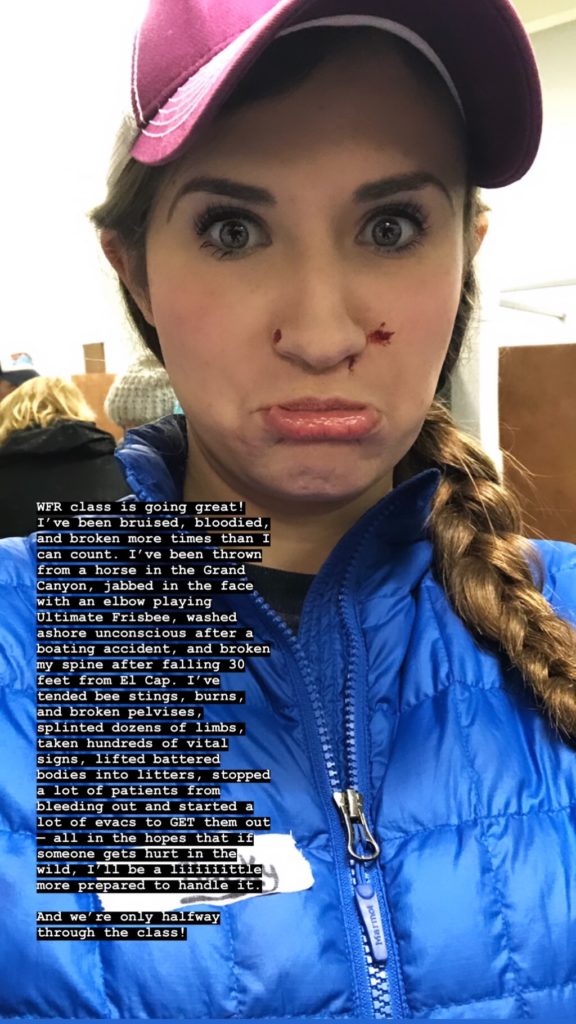

We wore moulage, aka stage makeup, to make the injuries feel more real. Puncture wounds, bruises, burns — the detail was impressive and really helped us get in the zone.

Endria lost an eye in a boating accident. Halfway through her treatment she threw another twist her WFRs’ way, asking “Will this hurt the baby?”

Wounds were hidden under clothing that wouldn’t “hurt” until the responder touched it, and if they missed it you might “die.”

Some of my classmates gave Oscar-worthy performances, somehow hanging on to the very detailed patient histories given by our instructors while adding in their own flair. (I, meanwhile, learned that I’m a terrible actor who has trouble not laughing while I’m supposed to be unconscious.)

I stumbled home every night with my brain still buzzing.

Our WFR class spanned all ages and experiences, from a 17 year-old who needed her WFR for a summer camp job to two retired friends who wanted to better care for each other on the trail.

There were grizzled professional guides who’d already led hundreds of humans into the wilderness, new guides prepping for their first gig, hardcore climbers and adventurers who’d experienced a close call or trauma and decided they needed this class, a woman who lives half the year among the Maasai people in Kenya, far from the nearest hospital….and me. We all bonded in the muddy trenches of Crissy Field, splattered with each other’s fake blood, and I came away with an amazing group of new friends.

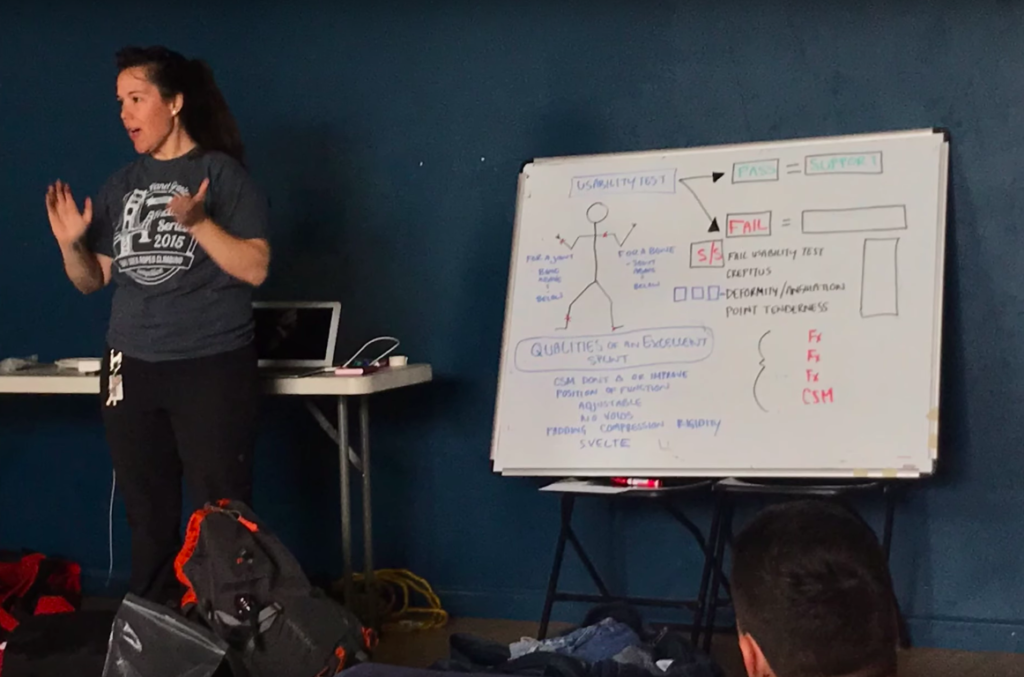

Like any class, your experience depends largely upon the quality of your instructors — and my instructors were bloody (moulage-y) fantastic. Nissa, a no-nonsense EMT with a winning smile, and Jessica, a savvy mountaineering guide who spends half the year in Switzerland the other half in the Eastern Sierra (#goals), had several decades of first responder experience between them. Our class hung on every word, eager to hear more gross/engrossing stories from their days rescuing climbers and tourists in Yosemite or riding in the back of an ambulance.

Our classroom made the experience, too. Half our time was spent in the yoga room at Planet Granite SF —a bright, happy place filled with active, happy people — and the other half outside on gorgeous Crissy Field, a grassy meadow on the edge of San Francisco facing the Golden Gate and the rolling emerald hills of Marin. The idyllic setting made playing patient a pleasure.

Once, lying on my back in a field of spring’s first wildflowers with the soft San Francisco sun on my face, I watched blue herons landing gracefully as startup employees played bubble soccer (not so gracefully) nearby. Suddenly an impossibly cute corgi was licking my moulaged face, having wandered over from the nearby corgi meetup.

In addition to indoor/outdoor courses like the one I took, NOLS offers immersive, overnight WFR courses where you actually go into the wilderness with your fellow students and instructors. It’s a more realistic experience, but a more exhausting one — I hear they even wake you up at 2AM to make the nighttime scenario more realistic! But, you’ll be bonded for life with your classmates in a way you can only be when you’re together 24/7 for several days straight.

A few times I opted to stay in the Presidio overnight and sleep in Ruby Sue rather than drive home only to turn around and drive back 10 hours later. Several of my fellow wannabe WFRs were dirtbags, too, with sweet setups in their cars for sleeping at the trailhead or the crag. It felt like stealthy sleepover. One of my fondest WFR memories is of tailgating by the Presidio Pet Cemetery (yes, really) with Victoria, a new friend and a guide for REI, washing down the drama of the day with a pair of cold beers during a rainstorm.

I brought my woofer, Juno, to WFR with me the days I slept in the car, leaving her snoozing happily in Ruby Sue during class and walking her along Crissy Field during breaks.

It’s impossible to summarize all the medical knowledge I learned in 80 hours of class, but here are a few global ideas that stuck with me:

– “Patients lie.” It’s not malicious and usually not even on purpose, but patients can’t always tell you what you need to know. Adrenaline blocks pain and emotional trauma distracts, so it’s important to take vital signs and do a full body scan even if the patient looks and “feels” fine — or is convinced that their broken leg/aching head/puncture wound is the only problem worth looking at.

– “Is this normal for you/them?” is a good way to assess potential medical clues. When you’re treating a stranger, it can be hard to tell the difference between someone who’s irritable because they had a bad day or are just a grouchy person, and someone who’s irritable because the candle in their tent is giving them carbon monoxide poisoning or because they fell earlier in the day and have a traumatic brain injury. The more info you can gather about a patient before/after the incident, the better.

– “All patients are diabetic until proven otherwise.” Our final exam involved a patient who was breathing but totally unresponsive, with no visible injuries. The solution? He just needed sugar. This simple answer was hard to come by in the moment — my partner and I nearly failed, as did most of the class — but it’s now one I won’t forget.

– “I’m number one!” On our very first day, the instructors showed us a news clip of a real-life rescue. One person had fallen through the ice, prompting many others to go after him and fall through the ice themselves. By the time first responders showed up, they had not just one victim but over a dozen! It’s the equivalent of putting on your own oxygen mask before helping others.

Who should take the WFR course? Is WFR right for me?

While it’s an amazing experience for anyone, WFR isn’t for everyone.

If you don’t plan to become a guide and just want some extra knowledge, a Wilderness First Aid (WFA) class is a great alternative.

A WFR is 80 hours of instruction and costs ~$775, while a WFA is just 16 hours and ~$245. The WFR takes 8-10 days while the WFA is usually taught over a single weekend.

That said, if you have the money and time for a WFR, I’d still highly recommend it. You’ll learn more, practice more, and have more fun! (In event of a real wilderness incident/zombie apocalypse, I’d rather have a WFR with me than a WFA.)

A WFR cert is required for many outdoor guiding positions, but not all. REI, for instance, only requires its guides to have a WFA. Some employers will pay for your WFR as part of training. If not, they likely pay WFRs more money than WFAs, meaning the course eventually pays for itself.

Not ready to invest a WFR class? You can still be prepared for your next adventure.

– Sign up for The Scenario, NOLS’ quarterly email newsletter.

It’s free, and you don’t need to be a NOLS alum to get it! Every email includes a sample emergency scenario drawn from real-life to get your emergency medicine wheels turning. Should you ever come upon a similar situation on the trail, you’ll be that much more prepared.

– Pack the 10 Essentials, including a good First Aid Kit, every time you go outside. (Yes, even on day hikes!)

Most serious incidents happen to day hikers, not backpackers, even though backpackers spend more time in more “dangerous” areas farther from civilization. That’s because day hikers don’t typically bring what they might need to survive a night outside. Stories abound of people going out for a “quick walk” that turns into multi-night misery (or worse) after an unexpected accident.

– Buy and bring a Garmin InReach.

The InReach is a 2-way messaging and SOS device you can use to call for help if something happens. Unlike other SOS devices, though, you can use it to send text messages back and forth in case of emergency. (You can also use it to text your loved ones back home — no emergency required!) Nearly all professional wilderness guides carry one on trips, and if you’re regularly entering the wilderness then you should, too.

While the InReach is great to have, you should still never assume helicopter rescue is available. Scarce resources, uncertain weather conditions, and other emergencies may prevent SAR from responding to you right away (or at all.) Helicopter flight is also dangerous for the crew who comes to help you and should only be used as an absolute last resort.

Using WFR skills in real life

At the end of our 10-day course there was a 100-question multiple choice exam followed by one final scenario. Everyone passed!

Unfortunately, my first opportunity to use my WFR skills would come just a few months later on the John Muir Trail. As I wheezed my way up the steep switchbacks on Mather Pass, I saw my dad and two other men up ahead, kneeling over a body face-down in the dirt.

“There’s someone hurt – stay there!” one shouted down, trying to shield me from the trauma.

“No, I’m a Wilderness First Responder!” I found myself replying. “I’m coming up.”

As I rounded the last slippery switchback towards the victim, I was frantically running through the PAS (patient assessment system) in my head. Sadly, by the time I reached him —and, it turns out, by the time anyone had— it was too late. He was still warm but had no pulse at all. There was nothing we could do.

As awful as that morning was, I was still thankful for my WFR training. It helped me stay calm, and gave me the peace of mind that I did the best I could in a tragic situation.

I want ALL of my hiking buddies to become WFRs now, especially if we’re going on overnight adventures together. You never know when a “scenario” will happen in real life.

Thanks to NOLS, ReadySF, and my talented instructors Nissa Guerrero and Jessica DeMartin for an amazing class! Thanks also to my badass classmates for the photos, and for patiently playing patient as I practiced my nascent WFR skills on them. Finally, thanks to Trail Mavens and to the amazing Trail Mavens guides, all woman-WFRs, for inspiring me to take it in the first place.

And, of course, thank YOU for reading! Hope to see you on the trail…where we will hopefully never need our WFR skills. 🙂

3 Comments

Leave your reply.